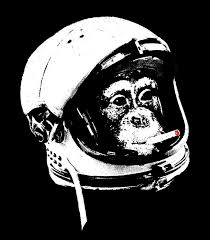

I stared at the chimpanzee, spellbound. A parade of majestic Mayan figures marched across his face carrying signs that made up a system of messages I found fascinating but impossible to understand. A lone, lithe figure dressed in iridescent greens and yellows danced gracefully above the Mayans. Simply amazing, I thought. The chimpanzee was wearing a helmet, a space helmet, and was projecting this ancient dance to me aboard my boat in the middle of the Caribbean Sea. Slowly one of the Mayan signs came into focus. EEO, it read. E, E, O, I thought. What in the world is that? I concentrated hard. I knew the answer was out there, and I was hoping it would come to life for me. I wanted so desperately to know.

Indeed the answer came swiftly and severely—like a bomb. The chimpanzee was in fact my cockpit bulkhead compass. The Mayan symbols were not parading across his face, they were the compass wheel revealing my bearing as Ave del Mar spun to the north. “EEO” was “330,” which meant I was 60º off course. The dancing man was simply the yellow-green of the central marker on the glass of the compass, his head the shield from the compass’ internal light. I was sailing, and I was hallucinating, somewhere in the middle of my second night without sleep and somewhere in the middle of the Caribbean Sea.

Sleep deprived heroes in books and movies wear this battle much more romantically than I did this starry night aboard my little boat Ave del Mar. I was sailing from Ile a Vache, Haiti, to Port Antonio, Jamaica, a quite doable distance of about 155 nautical miles. Somewhere in that first day of sailing the autopilot had failed in a kaleidoscopic display of lights and a cacophony of beeps and buzzes, and my attempts to repair it had failed despite the aplomb I thought I had displayed. No autopilot meant no help steering the boat, and no help steering meant no sleep.

There was a notable absence of drama in this event as Ave and I were hardly in peril. The seas were a bit lively but far from being dangerous. We weren’t falling down waves the size of city buildings, we weren’t fighting leaks that could sink the boat, and we weren’t without food or water. What we were was mired in an exercise of epic inconvenience.

Ave and I made good progress despite running under soft winds. I had the genoa poled out to starboard and pulled taut. So many of the mysteries that used to challenge me while sailing were comfortable old friends now, the drama of their newness gone from our relationship. Sailing without land to hit or shallows to avoid meant that the chart plotter stayed off for most of the trip, silently recording our track in the background while I sailed from the magnetic compass. As that first night fell, I opened the tablet to double check my progress. Ave was right where she was supposed to be but the navigation tablet’s battery was clinging to a charge of less than 10%, another dangerous inconvenience.

A little troubleshooting led me to realize that the USB outlet that powers the device had failed, so I rearranged some electronic assets and I plugged the tablet into one of the backup power sources. Happy to see it charging again, I knew that in the course of the night it would slowly come back to life. The battery charge on my backup navigation tablet was satisfactory to get me into port if needed. Catastrophe avoided.

That first night passed without incident. There were good moments of sailing, of stargazing, and of free thought flow. That is what nights at sea do when they are calm. Morning broke and I was feeling good about the trip and my ability to push through.

As the sun crept higher in the sky I started to realize that the absence of sleep was impacting my thought process, and so I started to think about what ways were available to me to catch a little shut eye. It was becoming clear that not sleeping was not a viable option, despite the good story fodder that it made.

I decided to heave to—a process of effectively stalling the boat just off the wind. This is an old and simple sailing trick that calms the boat’s motion and allows a respite from the attention that the helm requires. In short this involves arranging the sails in a conflicting configuration, each trying to turn the boat in an opposite direction. I have never had to heave to as a storm management strategy, but I have practiced numerous times for whatever the occasion may be, and this was the occasion.

After dousing the genoa I went forward to raise the mainsail, my safety harness responsibly clipped to the bright red jackline. Raising the main was also more complicated than one might expect, because I had no auto helm to hold the boat’s direction. To raise the mainsail you ideally want to point the boat right into the wind which renders the sail inert and makes it easier to hoist. Without a crew member or autopilot the boat wants to fall off as the wind blows the bow away, so you end up side to the swell which amplifies the boat’s rolling action rather dramatically and makes simply standing on the deck a risky undertaking. But I’ve been through this enough times, have feared for my life enough times, have braced myself while clipped to the jackline enough times that it really wasn’t the biggest deal.

The mainsail somehow went up, as I used the boat’s rolling action to offset the pressure of the wind. With the sail in need of tensioning I grabbed the winch handle, looped the halyard thrice around the winch, and started to crank. As the second crank began I was treated to an encore of my “Bahamian Flying Winch Drum” drama as the Australian-made Barient winch fell apart in front of my eyes and the drum flew off of the base. Unlike the Bahamian episode, this one did not smack me in the face and did not fall overboard, both welcome edits to the storyline. But with the second of only three mast winches now out of order heaving to was off of the table as an option. Sleep would have to wait.

A most-undramatic drama, this one, absent all of the squalls, winds, lightning, and heroic undertakings that lend color to the stories that sailors inevitably tell. “The Story of That Night I Didn’t Sleep” seemed a poor title for a tale. I wasn’t holding my breath for Hollywood to come knocking.

Throughout Tuesday I crept onward and the wind speed crept downward. By afternoon the winds were marginal at best, so I started the engine to power through the second leg of the journey. The genoa offered a bit of steadiness to the boat’s rolling action, and the 35 horsepower Universal diesel pushed Ave along at a slow if not steady pace of 3.5 knots or so. I could survive this, I reminded myself. No one ever died at sea from moving slow and steady in settled weather.

It was late in the afternoon when I noticed the unmistakeable sound of the engine RPMs plummeting as the diesel workhorse was being starved for fuel. The particulate was back—or, rather, the particulate was still there—and it was clogging the fuel line out of the tank and into the filters. For the first of six or seven times during this trip I shut the engine down, took apart the cockpit grates, and climbed down into the engine compartment to clear the congestion. With the motor off and the winds light the boat fell predictably beam-to and tossed violently side to side as I tried to hold onto tools and perform my diesel bypass procedure. At one point we rolled enough that my canvass bag of food which lives in the cockpit poured its contents onto my head and down into the engine bilge as I was draining the fuel lines. My prepared sandwiches fell into the murky bilge along with crackers, hard boiled eggs, and whatever else had been at the ready. I paused my fuel operation long enough to pull soggy food from the bilge water and fling it back out into the cockpit with a violent and angry cry. Things were starting to build up.

Onward I motored, onward I steered, and onward I checked the Racor fuel filter vacuum gauge for restrictions. Half of my brain said this isn’t so bad, and the other half brainstormed ways to sink the boat in the first Jamaican harbor I could find and buy an airplane ticket home. It’s a familiar tune on an old boat with the problems that come with boats and age. I remember fondly sitting with a young man in George Town, Bahamas, who was telling tales of making way through a cut that he had no business attempting to clear (yep, I’ve done that too). He confessed so effortlessly, as sailors do, that he almost hoped at one point that the boat would just hit a reef and sink because then the torture of trying to make it through the cut would be over. “No one who hasn’t done it will ever understand just how much you really mean it when you wish those things,” he said, deadpan.

It was in the early stages of the second night that the hallucinations began. They started mildly, not full on space-chimpanzee-and-Mayan-parade level but a simple detachment of consciousness. I would be motoring and staring at the compass when I would suddenly realize that despite looking right at it, I was allowing the boat to turn off course. The numbers just stopped conveying meaning to my brain and my brain stopped sending signals to my hands and everything got weird.

The detachment eventually gave way to a parade of confusing episodes where I couldn’t figure out what the compass numbers meant. Eventually I started to think that some of the numbers were actually words, and I would stare at the wheel trying to determine what it meant and how I should steer. I am navigating currently somewhere between ‘270º’ and ‘EFO.’ Hmmm. What to do, what to do. Reality was slipping steadily away.

Then Dancing Man appeared. He entertained me endlessly, sinewy figure moving elegantly side to side on the front of the compass, tall and thin in an elaborate carnival costume. He seemed so happy and carefree that he brought a sense of carefree to my night. Rarely during that time did I realize that Dancing Man didn’t really exist. There was no ebb and flow into and out of awareness, no moments of Oh! I was hallucinating again. Just me and Dancing Man motoring slowly westward, he with his big hat on and me smelling of diesel.

Every few hours I had to dig deep enough to find the ability to climb down into the engine compartment again to drain the diesel lines of their sediment. This, too, became less of an ordeal. I was Job, and my duty was to persevere. I didn’t want to drain the diesel. I didn’t want to sit in the cockpit confused. I just wanted to see my anchorage in Jamaica magically appear before my eyes, to have a shot of rum and go to bed. I wanted this desperately.

I had long lost contact with my sailing companions as they were both out of VHF radio range. As Tuesday night gave way to Wednesday day I could occasionally hear enough to know that they were out there talking with each other, but the words were merely indistinguishable background noise. Ave del Mar and I trudged on, progress slowed by our erratic route as we twisted and turned off of our desired course. By the time I made landfall in Port Antonio we had added about 12% to the length of the journey by virtue of our wanderings. So goes life.

When I was a young boy my family regularly vacationed in Colorado, camping in summer and skiing in winter. We would drive west on I-70, the five of us in our 1965 Microbus, my father commenting that we were the only vehicle that the tractor-trailers ever actually passed going uphill in the Rockies. Somewhere in Colorado the Rocky Mountains would cut the horizon and I would get so excited. The mountains! I would think. We’re almost there! Throughout that day of slow westward driving the mountains proved elusive. On and on we drove. The mountains were some sort of evil depth perception trick. Jamaica rekindled that struggle in me during the daylight hours of Wednesday as I could see the mountainous skyline of the Jamaican shore, but it never seemed to actually grow closer.

As we know, though, it did draw nearer and late in the afternoon of Wednesday I entered the channel towards Errol Flynn Marina to clear customs and immigration. I was too tired to be relieved. Again I dug deep, concentrating hard as the numerous officials climbed onto my boat and I completed form after form to clear in. I asked questions. I confessed readily and rapidly that I was in a compromised state from lack of sleep. The officials were all professional, friendly, courteous, and helpful. Eventually the parade of red tape ended and I paid for two nights in the marina. Untying to go anchor was more than I could begin to imagine doing. I walked down the dock to my friend Aldo’s boat where he was engaged in a lively conversation with a young French man who had hitchhiked into town on a Dutch catamaran.

“Aldo,” I said, “I am going to walk to THAT bar”—I pointed to the poolside bar—“where I am going to eat something and drink Red Stripe until I am drunk. I am leaving in three minutes, with or without you.” I drifted back to Ave where I put on a decent shirt and grabbed some money, and I was back at Aldo’s boat in short order where nothing had changed. Shirtless Aldo still sat on his coach roof chatting with the nice French lad. “I will save you a seat and I will buy you a beer,” I said, “because I am going right now.”

Walking alone towards shore along the dock I was soon joined by Aldo who scrambled, commenting to his new French friend on the insanity of the American man he had chosen to sail with. I paused, and we walked together. Grabbing a seat at the bar my first Red Stripe fell quickly away. I snapped a quick photo which went up on social media to announce to the world that I had arrived, arguably alive, in Jamaica. The beer tasted good.

Aldo told me in his broken English that I drive him crazy. I listened to him, as another Red Stripe and a plate of food came and went.

Soon enough Aldo refused another beer but I forged forward without him, solo sailing again, happily and deeply and at the perfect pace.

2 responses to “Space Chimp and the Jamaica Crossing”

Best post yet!! Glad you survived little bro!

LikeLike

❤

LikeLike